Manila to relocate 500,000 informal residents ... but to where?

The Philippine government is planning to demolish 104,000 homes across Manila, clearing its waterways and rehousing informal settlers outside the capital region. Everyone involved in implementing the plan knows that this is a bad idea, that it will destroy livelihoods and will waste millions of dollars on futile construction work, yet we have no international framework to stop them going ahead.

The Philippine government has pledged to demolish the homes of 500,000 people in (Metro) Manila, and relocate residents to new low-cost housing developments on the fringes of the region.

Ostensibly the purpose is to clear the city's clogged and polluted canals and rivers that contributed to two-metre high flooding in several areas during Typhoon Ketsana (known locally as Typhoon Ondoy) in 2009. But as the city's authorities know very well, the manner in which a hundred thousand families are being uprooted from their sources of income and support networks will cause economic destruction of arguably greater severity over the long term. So why aren't alternatives being pursued more earnestly?

As Paul Mason of the New Statesman reported this month, the National Housing Authority (NHA) has ruled out the possibility of rehousing the 104,000 affected families within their current neighbourhoods. They argue that rehousing all of Manila's estimated 540,000 informally settled families (perhaps some 2.7 million residents) within their existing neighbourhoods would cost the equivalent of one-third of the government's annual budget of 1.8 trillion PHP (42 billion USD/26 billion GBP).

The NHA knows that these sites make life economically unsustainable, and know that residents are creeping back to the city and squatting elsewhere.

Instead, affected families will be housed in single-storey developments in the rural fringes of the metropolitan region, anywhere between two and four hours away (one way) by public transport. Far enough away, in other words, that residents are being forced privately to decide between accepting the house and losing their jobs, or keeping their jobs and finding somewhere else to squat in the city.

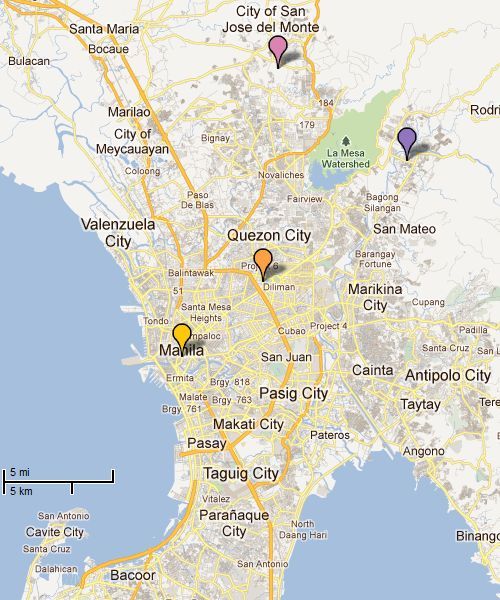

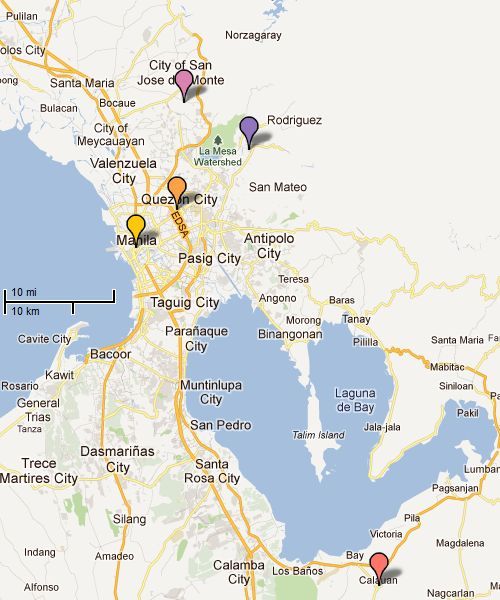

The maps below show two of the largest centres of informal settlement currently due for relocation: the canal and commercial district of central Manila and the North Triangle redevelopment site in Quezon City. They also show three of the largest resettlement areas: San Jose del Monte and Rodriguez (formerly known as Montalban) near the wilderness to the northeast, and Calauan on the far side of the lagoon to the southeast.

The location of esteros in central Manila (yellow); the North Triangle redevelopment site in Quezon City (orange); relocation sites in Barangay Gaya-gaya, San Jose del Monte, Bulacan Province (pink) and Rodriguez, otherwise known as Montalban, Rizal Province (purple). Source: Google Maps

The location of Calauan, Laguna Province (red) in relation to the other sites. Source: Google Maps

Satellite photo showing the location of San Jose del Monte (pink) and Rodriguez (purple) on the fringes of the Manila metropolitan region bordered by wilderness, in relation to North Triangle (orange) at the edge of the urban core. Source: Google Maps

The NHA knows that these sites make life economically unsustainable, and know that residents are creeping back to the city and squatting elsewhere. Really the government should abandon the pretence that these sites are viable solutions to Manila's housing problem, and commit themselves to designing and financing a programme to rehouse all informal residents "in-situ", that is, in the same neighbourhoods as their existing settlements.

But the argument that these relocations destroy the livelihoods of affected families is made a thousand times inside and outside Manila's corridors of power to no effect. So let me suggest a different approach. Most relocated families send their husbands and fathers back to central Manila to work, forcing thousands of men to seek additional accommodation and to see their families only once a week or fortnight. Yet some 30 to 40 per cent of families abandon their houses entirely, or return only once a month or so to maintain the pretence that the building is inhabited.

... there is no international framework capable of intervening when the human rights to housing and freedom from evictions are being flouted.

This 30 to 40 per cent of houses means money spent in vain by the government. If Manila carries through with rehousing 104,000 households at a cost of 175,000 PHP each (4,100 USD/2,500 GBP), they will be wasting at least 5.46 billion PHP (128 million USD/79 million GBP) constructing houses that they know will be unoccupied. Why does the Philippine government want to spend 78 million pounds on building empty houses in the wilderness?

If on the other hand the government were to spend the 115 billion PHP (2.7 billion USD/1.7 billion GBP) it implies is required to house these families "in-situ", to my mind that would be money well spent. Think of how many new construction jobs would be created if 1.7 billion pounds were committed to apartment-building over the next five years! Think how many underemployed Manileños would develop new skills! Think how many economies of scale would be discovered across the sector!

As for the private landowners who would be forced to sell their unproductive inner-city lots for such a scheme, think how much they could suddenly reinvest in expanding the manufacturing and services sectors of the economy! The government would need to pay them in PHP-denominated bonds or use other controls to keep the cash circling in the local economy, but the thousands of households enjoying stability and savings capacity for the first time in their lives would generate huge consumer demand for new commercial opportunities.

In any case, the costs for "in-situ" housing calculated by the NHA are too high — it could be reduced dramatically with just a little bit of political imagination and historical insight. Manila's leaders often look to Singapore's clean streets and slum-free districts as a model for what they hope their city to look like. Why isn't more being learned from Singapore's housing policy as well?

The Philippines is as wealthy today as Singapore was in 1975, at which time Singapore was committing a modest 2 per cent of its national budget to a universal housing programme which by 1990 had successfully seen 85 per cent of Singapore's population housed in public sector schemes. The Philippines is not too poor to house its people sustainably, it just needs to look around for more creative solutions.

As Mason's article showed, the NHA is trying to coax informal residents to these new-build outposts with promises of running water, functioning sewerage and stable electricity. Gina Lopez, head of the ABS-CBN Foundation partnered on the project, is hiring select squadrons of squatters to patrol the newly-cleared canals to prevent new settlements reforming.

Their attitudes are backwards on both counts. Firstly, if informal residents were attracted to water, sanitation and power, rather than to bustling job markets, they would never have left the countryside a generation ago in exchange for the precarious lodgings of an inner-city slum.

Secondly, more people will keep coming to the Philippines' cities, and that's a good thing. There is a correlation between a country's average income level and the proportion of its population living in urban areas. Whatever the causality, if the Philippines expects to be more developed in the future, then it should also expect to be more urbanised. Rather than trying to stall future arrivals, Manila, Cebu, Davao and other cities must be ready now to cater for greater and greater numbers of arrivals.

Whether the capital should be expected to carry the lion's share, or whether urban migration should be directed towards other cities is a matter for a separate debate. The point is that the only way the Philippine government can reshape the long-term trend toward further urbanisation is by attracting it towards alternative centres of economic growth. Promises of running water and mains power in far-flung suburbs is not going to change that.

The other question that must be asked is what can be done internationally to prevent man-made disasters of the kind being proposed by the Philippines government? What can UN-HABITAT, the United Nations' lead agency on cities, do? What might the World Bank's Cities Alliance do? What about the Asian Development Bank, whose headquarters are in Manila? Despite all the good intentions of agencies such as these, none of them have a mandate to contravene the actions of national governments, and as a result there is no international framework capable of intervening when the human rights to housing and freedom from evictions are being flouted.

In the 1970s when President Ferdinand Marcos was preparing to evict thousands of residents from portside districts, residents appealed to the German magazine Der Spiegel, whose coverage caused German investors and donors to criticise Marcos' plans and pressure him to house those communities within their existing neighbourhoods. If this is the only kind of pressure a government will respond to, then we need institutions that can apply that pressure every time it is needed. Not organisations whose only legal mandate is to advise and consult with national governments at the pleasure of the latter.