What's a national urban policy for? Three scenarios for Australian cities

In the first of a two-part response to the Australian national urban policy, Kerwin Datu discusses the role of national policy in setting the strategy for the national urban system--the balancing of small, medium and large cities--and points towards a 'global city' future for Australia's regional cities and outer suburban centres.

Australia is one of the most urbanised countries in the world, with 88.9% of its population living in cities at 2009. Apart from tiny countries like Belgium and Kuwait, the only countries more urban are Argentina (92.2%), Uruguay (92.4%), Venezuela (93.1%) and Iceland (93.3%). Being so obviously urban, Australia could long take it for granted that its portfolio of cities were adequately managed by its state governments, since much of state politics was urban politics by default.

Nevertheless in 2008, the Rudd Labor government brought Australia's cities into sharper focus with the creation of the Major Cities Unit, under the Department of Infrastructure and Transport. And late last year it released its discussion paper, Our Cities: building a productive, sustainable and liveable future, opening a (rather muted) public debate on the national urban policy.

The discussion paper, and the background research that went into it, have brought Australia well up to speed with the discourses that dominate sustainable urban planning in Europe and North America, in areas like innovation policy, resource security and social inequality.

Is Australia drifting inexorably towards demographic growth concentrated in a few sprawling cities, or smoothly redistributed across our secondary centres?

Yet there is one fundamental role that policy must play which I believe is overlooked in the discussion. A national policy is needed to set the strategy for the national urban system — the balancing of small, medium and big cities across the country. Is Australia drifting inexorably towards demographic growth concentrated in a few sprawling cities, or smoothly redistributed across our secondary centres, and should Australians have a say in the direction of these long term trends? Depending on the decisions made, a national policy may tip the balance heavily in favour of big cities, or small cities, in ways that individual places are ill-equipped to plan for in isolation.

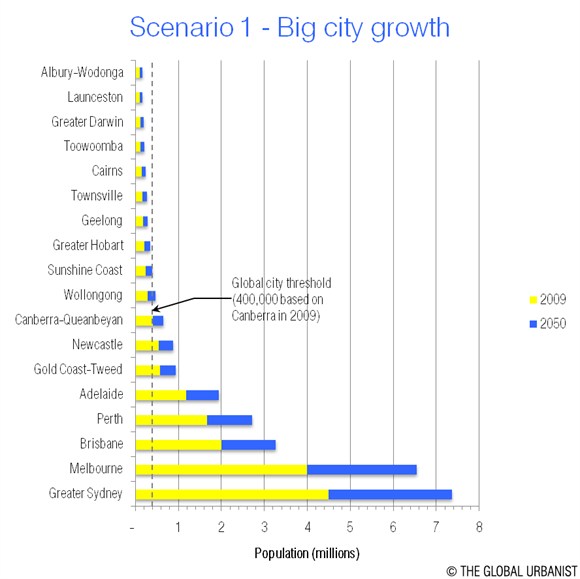

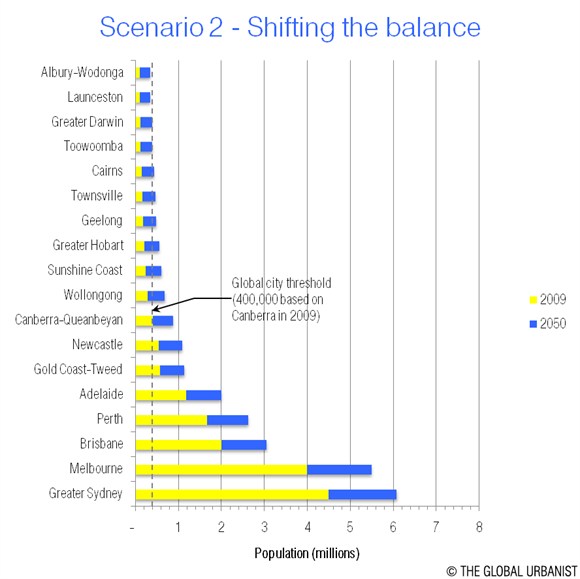

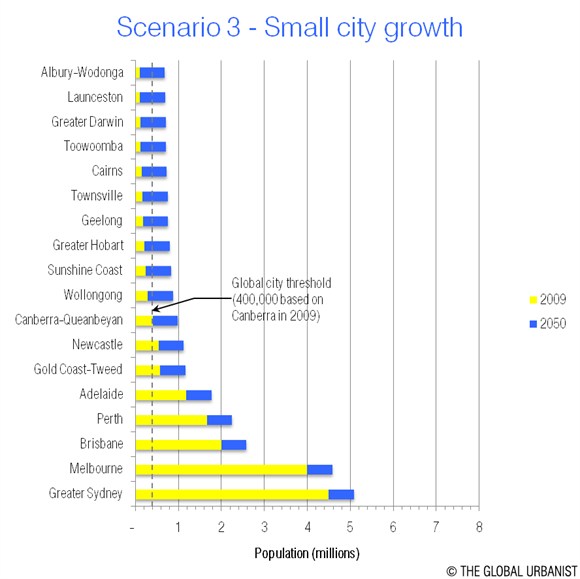

Consider the three scenarios below. Australia's population is expected to grow from 22 to 36 million over the next forty years. Each scenario depicts a different way of spreading the urban component of that growth over the 18 largest cities (those currently over 100,000 in population). In each case a population threshold of 400,000 people is indicated. This is a nominal threshold at which an Australian city arguably starts to become competitive as a 'global city' within the world economy. This is based on the notion that Canberra-Queanbeyan, with a population of 400,000 in 2009, is already classified as a city of 'high sufficiency' within the global economy according to rankings produced by the Globalisation and World Cities Research Network. (More on this on Thursday.)

Here all cities are given the same growth rate; as a result Sydney and Melbourne's growth in absolute terms is far greater than any other city, with the next big three also pulling ahead. Yet even here Wollongong and Sunshine Coast join Gold Coast-Tweed and Newcastle in surpassing the 400,000 threshold, creating four more cities that by rights should begin finding a real niche for themselves in the Asia-Pacific economy.

Here the growth is partially distributed. Gold Coast-Tweed and Newcastle cross the one-million mark, while Greater Hobart, Geelong, Townsville and Cairns cross the 'global city' threshold.

Here the total population growth is completely redistributed — all cities receive the same absolute population increase. In this scenario there are over a dozen new cities with the capacity to become players in the international economy.

The question is, which scenario is the most likely? Which is the most ideal? While Scenario 1 may seem the most intuitive, nothing prevents two or three of the smallest cities from bursting ahead over the pack in a manner befitting Scenario 3. And there is also no reason to expect that Sydney and Melbourne will continue to grow as smoothly as they have in the past. A good precedent is in Brazil, where growing pains in Sao Paulo caused businesses to break out towards smaller cities in its hinterland where productivity could be maintained without suffering the same costs of congestion and lack of planning. It is possible that in the attempts to pack another two million people each into Sydney and Melbourne over the coming decades, a great number of businesses and residents grow frustrated and choose to fill up neighbouring regions such as Wollongong and Geelong instead.

These movements suggest that small and medium-sized cities like Hobart, Townsville and Albury-Wodonga should absorb the lion's share of the expected demographic growth, not the big five.

Population growth and ageing

To choose which scenario is ideal is beyond the task of one writer like myself; nevertheless the basic demographic trends suggest that Australia should seriously consider the third scenario. Apart from substantial population growth, the ageing of the population creates two spatial challenges: the reduced average mobility of the population, and the increase in populations seeking to retreat from the big cities. This has two basic consequences: more people will be living in smaller cities, and a significant proportion of the people remaining in larger cities will be moving in much smaller circles within them.

These movements suggest that small and medium-sized cities like Hobart, Townsville and Albury-Wodonga should absorb the lion's share of the expected demographic growth, not the big five. It also suggests that the big five cities need to be reconfigured, with a more concerted effort to create real multicity regions, not the tokenistic 'polycentric city' model often proposed. In practice this means developing centres like Parramatta and Dandenong to the point where their economy and services can operate independently of central Sydney and Melbourne in several domains.

Given that there is also sharp potential for easy productivity gains in doing so, there are strong reasons for shifting residential and commercial demand to these secondary centres, and for a national urban policy focused on expanding the resource, planning and development capacities of these cities where it can be done sustainably. I think it's time to bring these cities out of the shadows of the big five.

From this Thursday, read the second part of this article - Coming out of the shadows: connecting Australia's secondary centres.