DfID withdrawal from UN-HABITAT displays naivety on slums

DfID's decision to withdraw its voluntary funding from UN-HABITAT and other UN programmes demonstrates an ignorance of the contradictions present in the mainstream development agenda, and the intractability of the problems facing urban areas.

The United Kingdom's Department for International Development (DfID) recently completed a major review of its funding of multilateral aid agencies, which tried to identify which of 43 agencies represent the best "value for money" for the UK taxpayer, in terms of their contribution to UK development policy concerns and the mainstream international development agenda. One outcome is that it has retracted all voluntary funding from UN-HABITAT, the United Nations' lead agency on urban development issues. (For full disclosure: I am currently engaged in a minor role as a consultant to UN-HABITAT on its website initiatives.)

The review places a major emphasis on each agency's accountability and transparency on how it spends donor funds. There is a fundamental question as to whether the needs of the developing world are best defined by the UK taxpayer, or by the collective constituency of the developing world itself. But there is also a question as to whether the transparency of agencies themselves are the best measure of the "value" that they offer for the progress of international development. An agency such as UN-HABITAT may suffer from weak internal accountability management, but does far more to improve the transparency of governance at the local level worldwide than it lacks in the transparency of its own finances.

Despite the well-known demographic trends, much of the mainstream development industry still have trouble seeing that cities need their attention.

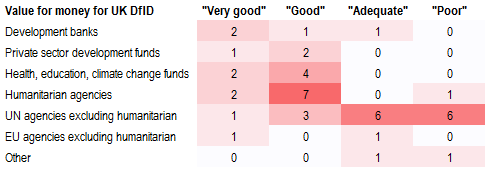

While the review claims to spell out its decisions using objective criteria, it does skew heavily towards a certain kind of organisation. Large financial institutions and on-the-ground, humanitarian agencies are in, United Nations programmes are out. As the following heat-map table shows, the bulk of UN agencies represent merely "adequate" or "poor" value for money for the UK taxpayer; few other agencies fare so badly.

This sends a clear message that money and action count, thinking and talking don't. Sound fair? Only in a very short-sighted world. Most UN programmes were created at moments where the international community realised that specific issues were falling through the cracks of the international development architecture — issues like women, migrants, food security, cultural development, and of course, urban areas.

The most important role that these programmes play is to monitor and research how these "minority" issues are evolving around the world, and bring this knowledge to the attention of the mainstream agenda. Like minority organisations everywhere, they are small, systematically underfunded and neglected by the powers that be. It is unfair and unthinking to assess them by the same performance measures as large development funds and crisis relief agencies. In the same vein, it is questionable to assess all UN programmes on the basis of the mainstream development agenda. By definition, these programmes address areas that fall to the margins of that agenda, and in some cases contradict it.

The latter is certainly the case for UN-HABITAT. Despite the well-known demographic trends, much of the mainstream development industry still have trouble seeing that cities need their attention. Time and again, development researchers returning from disaster-stricken areas like Haiti, Sri Lanka and Aceh complain that too many humanitarian agencies avoid working in cities because they are too complex. Just look at how Port-au-Prince has languished in the past fifteen months. It's far easier to demonstrate "results" to accountability-obsessed donors like DfID by working in rural areas where houses can be thrown up, pit latrines dug and vaccinations distributed in great numbers without wading through the intense politics and regulations that constrain action in urban areas. Seen in this light, UN-HABITAT's seeming underperformance is due to the high degree of difficulty that it must operate within, and its insistence on tackling complex problems, not repetitive ones.

Despite everyone's best efforts, slum settlements still proliferate around the world, and the mainstream development industry persistently underestimates the problem. One of the world's leading researchers on urban settlements, David Satterthwaite of the International Institute for Environment and Development, lambasts agencies like the World Bank for systematically miscalculating poverty rates in urban areas. Within cities, non-food and monetary costs are usually far higher than in rural areas and greatly surpass the assumptions used in constructing poverty lines like the proverbial "dollar a day". While nominal and average incomes may be higher in cities, the real earnings of the urban poor are often far worse than their rural counterparts.

With his growing interest in climate change [Clos] is reaching out more aggressively to the mainstream development community. But he also risks shifting the focus ... towards more fashionable and cacophonous debates where UN-HABITAT has no intellectual advantage.

The Millennium Development Goals, which drive much of the mainstream agenda, are also famously inadequate in understanding the slum problem. They call for "a significant improvement in the lives of at least 100 million slum dwellers" by 2020. This target has already been met, but only because it was set so abysmally low in the first place. While at least 100 million slum dwellers' lives have improved, this is not to say that they no longer live in slums! Even the most conservative estimates admit that there remain at least 830 million slum dwellers in the world, the vast majority seeing no improvement in their lives year on year, and their number continuing to grow.

The same cohorts of researchers who criticise the mainstream agenda for underestimating urban poverty criticise DfID for failing to show leadership on urban development, though to be fair they have said the same for UN-HABITAT on occasion. But DfID appears to be of the opinion that the problems of urban development may be refracted through other areas — water, sanitation, transport, etc. — and its belief that UN-HABITAT's mandate can be addressed by other organisations follows quite naturally. Yet it is exactly this attitude that a city is no more than the sum of its parts that cause other organisations to go in, go about business like they would in a village, get bogged down in urban politics, then throw their hands up when it all gets too hard.

The problems of urban development need an agency capable of understanding how different technical systems interface within cities, and how they are embedded within deeply-rooted social and political structures. What is missing from a sector-by-sector approach is an explicit focus on the special classes of dysfunction that arise within cities — the dysfunctions of property and land markets, of municipal governance, of social fragmentation and animosity, and of the urban monetary economy. UN-HABITAT has worked hard to bring these issues to light, and has made great gains in convincing municipal leaders throughout the developing world that they must be addressed holistically. In addition, its biannual World Urban Forums gather thousands of participants, over 10,000 at the 2010 session, making them some of the largest knowledge-sharing events on the international development calendar.

In these efforts this agency must counteract the effects of decades of anti-urban policies promulgated by mainstream development organisations, whose answers to urban poverty often consisted of telling slum dwellers to go to the countryside, where rural development projects offered them sparse and unsustainable employment in industries likely to suffer declining terms of trade once the country's economy finally took off. It is sad that UN-HABITAT must still answer to the scepticism of agencies like DfID in an era where even mainstream economic science has discovered the centrality of cities to development.

UN-HABITAT is not an innocent party in this discussion. Many of DfID's complaints, taken at face value, are valid. While UN-HABITAT has generated enormous energy within the urban development industry, and increasingly garners the attention of high profile private sector sponsors, it has failed to articulate its purpose to a wider donor audience, and it has failed to redefine the mainstream agenda in the way that health and gender groups before it have done.

Its new executive director, Joan Clos, comes with great administrative experience as the Mayor of Barcelona, but his mettle has yet to be tested as an effective advocate for the world's poorest cities and slum residents. With his growing interest in climate change he is reaching out more aggressively to the mainstream development community. But he also risks shifting the focus from the most enduring problems of urban settlements, livelihoods and governance towards more fashionable and cacophonous debates where UN-HABITAT has no intellectual advantage.

As important as climate change is, the complexities of improving living standards for the half of humanity living in cities deserve an agency wholly devoted to understanding them, not shoehorning them into other agendas, and that agency deserves the support of the international donor community, whatever its immediate inadequacies.

As one senior researcher at UN-HABITAT has put it, if the UK just doesn't have the money this year, let it simply admit that it doesn't have the money, without going to the trouble of defaming a whole raft of agencies who by the nature of their fields must take a longer-term approach to goalsetting.