Mapping the way to a more accessible bus network

A detailed, comprehensive and legible bus map system is not just for tourists. Bus maps also play a major role in making transport accessible to all kinds of locals and visitors, and ultimately in drawing people into greater engagement with the city they live in.

My uncharacteristically personal rebuke against London's bus stop 'spider maps' last week drew strong and mixed reactions from readers here and abroad. I will try here to contextualise my sentiments with a broader discussion on the role of bus networks in cities with mature urban rail systems.

One reader remarked that I had misunderstood this role: London's buses were not meant to get people from one side of the city to the other, but to act as feeder routes to and from rail interchanges to complete the 'first' or 'last mile' of one's journey.

Firstly, this is contradicted by the vast number of bus routes that clearly do cross the city from one side to another; secondly, a bus system is not and should not be intended for only one type of journey, or one type of modal interchange.

The roles of a bus network must be considered in light of its two main complementing systems, the urban rail network (tube, metro, subway, etc.) and the car.

An accessible and civic alternative to the tube

A bus system should not be subordinate to a rail system, but its complement. Bus networks fill in the detail of the rail system, and should be a faster alternative to rail where the road layout is more direct than the rail layout. This is possible even in parts of central London since the introduction of the congestion charge.

In many cases they will run perpendicular to rail lines, providing the missing link between stations on different lines. But in many others they will run parallel to rail lines to offer a faster alternative when taking the tube for one, two or three stations is too much hassle.

Taking the shortest trips out of the tube system helps with congestion; buses also help decongest the rail network during disruptions or spikes in commuter traffic. A bus system is more responsive to transport demand at several time scales: on peak days more buses can be added along major corridors (or indeed across them) and over time new bus routes can be established more easily than new underground routes.

There are also many groups of commuters for whom rail travel is often inappropriate. These include parents with prams and strollers, people in wheelchairs or who use walking aids, or have other mobility restrictions. Many people have legitimate phobias about underground travel or enclosed spaces. These users should not be forced to negotiate the narrow tunnels and staircases of an underground rail system, not least of which because they make evacuation extremely difficult in emergencies. The bus system must happily accommodate all of these users for as far as they need to go.

There is a civic argument that travelling above ground rather than under it is a more engaging way to commute, since it allows people to breathe fresher air, (especially if the bus is hydrogen-powered!) discover new neighbourhoods and aspects of the city, and offers more spontaneity to people's movements. These are small-order human rights compared to health, education and livelihood, of course, but they should not be denied because of narrow design thinking.

Using the bus to beat the car

When it comes to beating car dependence, a good bus network is not just about getting people in to work and out home again. That is important too, certainly, and the remedies such as bus lanes and congestion charges are well known.

But many people keep to their cars because of all the small errands that must be done on the way home from work or school — shopping, sports trips, music lessons, medical apopintments, dropping in on friends and relatives, etc. Getting these users onto public transport means convincing them that the bus network is detailed and interwoven enough to replace each small leg of their complex itineraries, and do it faster and more conveniently than a car, especially in suburban areas where the rail system inevitably thins out.

Laying out the journey

What does this mean for bus maps? It means that bus maps always need to show how complex itineraries may be made throughout the network, not just from A to B, but from A to B to C to D to A again. They need to show how the bus system relates to the rail network, so users can see which system is faster and when. But they also need to show how the bus network relates to the road network so that car users (amongst others) can see how much of their tasks can be achieved by bus. And they need to show these things at every bus stop.

Some of last week's readers will be thinking, "but only tourists need all this, residents know where they're going, or they've worked it out in advance." Here I need to apologise for focusing too much on tourists in last week's article. I was trying to appeal to an international readership, using landmarks that anyone anywhere would know, but instead I believe I misled readers into thinking that my complaints were only about tourist navigation. They were not; I could have made the same arguments using universities, theatres, shopping centres, schools or major redevelopment areas.

Again, I must urge those readers to consider all the different kinds of commuters, and how different their navigation needs are. And it must be said that residents don't always know where they're going! It can take years for new residents to learn their way around the city, and they'll need maps to guide them until they do. Residents new and old are always going to new places, as habits and routiens change, or simply to explore the city and learn new ways through it. From time to time, normal routes will be blocked, and new itineraries must be found.

Some people, no matter how long they've lived in a city, never quite grasp its layout for want of spatial comprehension skills. Many cannot afford or come to terms with smartphones that might offer beautiful navigation tools, or have the wherewithal to check directions at home and print them out before travelling. A mapping system should not punish people for lack of spatial confidence, or unpreparedness, or technophobia, nor frustrate spontaneous travel.

For those who don't know much about the area around their destination, or the area they're in to start with, bus maps need to offer multiple visual cues — landmarks, street hierarchies, major topography — to give people confidence that they've worked out where they are, and where to get off.

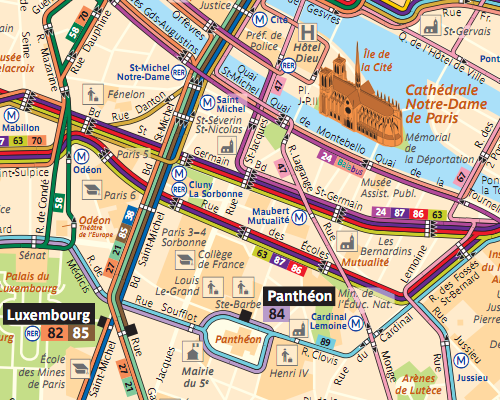

Other readers might now be saying, "a map designer can't do all this! They have to be selective, take decisions, make compromises!" Well, they don't really — certainly not as many as are made in London's spider maps. The Paris bus map I showed last week ticks every box I've asked for, which is why I keep showing it. Here is another extract, showing the routes around the Latin Quarter:

Source: RATP

Paris' bus maps offer designers three complementary strategies:

1. When you've got a panel the size of a bus shelter, use it. Make a really big map that shows all the detail you want, and it will still be legible once users have identified the locations that matter to them.

2. Display a range of maps: every bus shelter shows the whole network map I've described, as well as small inset maps of the nearby streets. They show long, skinny maps for each individual bus route that show every bus stop and cross street along the route by name. And they have diagrams showing how much of the whole network is operating at night time and on weekends.

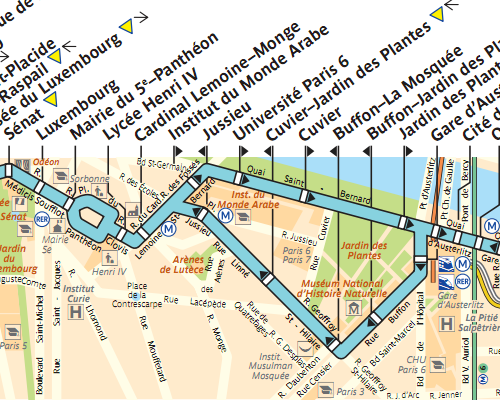

3. Accompany the rider throughout their journey. Most bus map systems wave you goodbye once you're on the bus, where arguably you need them the most. Every bus in Paris has those individual bus route maps inside the vehicle, so riders can track their journey, count the stops and identify streets or landmarks as they pass. Here is route 89 through the same part of Paris:

Source: RATP

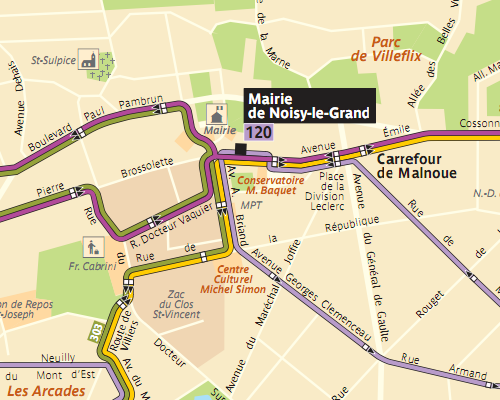

This level of consideration stretches right to the outer suburbs of the city, as the following excerpt covering the outer eastern suburb of Noisy-le-Grand shows. Earlier this year the Paris transport authority RATP assumed control of London United, one of the private companies operating London's buses. It might rub Londoners the wrong way to see Parisians rebranding the double-decker bus, but perhaps it's worth letting them have a go at remapping the network at the same time.

Source: RATP