Health and sanitation is an economic right as well--just ask Ghanaian food sellers

Continuing our series on urban livelihoods with WIEGO, Laura Alfers investigates the chop bar owners of Accra. Whereas governments are quick to scapegoat them for diseases borne by their food, in reality they spend onerous sums of money on sanitation, an effort which should be supported by urban health policy.

The urban planning and public health domains, once inseparable, parted ways after the 1940s. In recent years there has been a move to reintegrate the two — an example is the work of the Global Research Network on Urban Health Equity. However as Caroline Skinner has already pointed out in this series, the focus of recent research has tended to be on the city as a living space, where citizens' rights to adequate housing and basic services are considered, but where the idea that these same spaces are also workplaces is not fully engaged with.

Skinner argues that the provision of basic urban services needs to be seen as an economic right as well as a right of citizenship. This is just as true of health and sanitation policy, which has a direct impact on urban livelihoods as the informal food sellers of Accra show.

Scapegoating the food sellers

However what seldom arises in this discourse of blame is a questioning of the structural and infrastructural issues that leave food sellers with little choice but to prepare and sell food in an unhygienic environment.

Since precolonial times, urban trading has been an important part of the Ghanaian economy. In recent years it has contributed significantly to women's employment in the country, making up approximately 37.5 per cent of total female employment, according to economist James Heintz. Within this, the provision of cooked food has always been important. The British colonial regime, for example, relied heavily on local women's cooking to feed the labour force, and many of Accra's citizens and workers continue to rely on them today for tasty and affordable local food.

However, this has always been an ambiguous relationship. While colonial officials understood the value of sellers of cooked food, they also saw these women as a source of disease — my own archival research shows that Accra's colonial sanitation court records are packed with the names of women food sellers.

Little has changed in postcolonial Ghana. Informal food sellers are still blamed by everyone from fellow market traders to government public health officials for high levels of gastrointestinal disease in the country, and frequently find themselves having to pay fines to environmental health officers. However what seldom arises in this discourse of blame is a questioning of the structural and infrastructural issues that leave food sellers with little choice but to prepare and sell food in an unhygienic environment.

The provision of basic services in Accra is notoriously bad. Rigid structural adjustment during the 1990s privatised most basic services; the provision of water, refuse removal, and even the toilets in public areas have bee outsourced to private firms by the Accra Metropolitan Assembly (AMA). Yet this seems to have done little to improve the overall situation. Large open drains run through the city and are often clogged with refuse, modern sewage systems cover only a small proportion of the city, and the rivers that run through it are thick with grime.

The cost of providing sanitation unaided

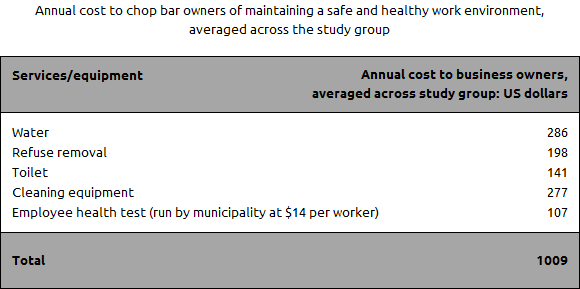

In 2010 the Occupational Health and Safety in the Informal Economy project of the global research and advocacy network Women in Informal Employment: Globalizing and Organizing (WIEGO) undertook a small study of 20 established food sellers — commonly known as 'chop bar' operators — in Accra to find out how much they spend to maintain a clean and health work environment in this context. The findings are summarised in the table below.

Total water costs were actually calculated at $572, but this number was halved to exclude water used in soup preparation. Therefore this may well be an underestimate.

The table shows that the chop bar operators spent just over $1,000 per year to maintain a clean and healthy environment for their business. This was over and above the various taxes they paid, which included a national revenue tax, a local business licence, as well as a daily tax paid by some operators. All of this adds up to a significant annual cost for what are essentially very small businesses. In a country where the national statistical services estimates the average income in urban areas to be $1.50 per day, it is not surprising that food sellers — many of whom are much poorer than the more established operators interviewed in this study — cannot afford to cook their food in a sanitary environment.

Improved recognition must necessarily include an understanding that basic urban services such as sanitation, access to clean water and waste management are part of a system of economic rights.

Governments and food sellers together

As currently framed, urban health regulations in Ghana do not 'see' traders and chop bar owners and their employees as workers who operate in public spaces. Regulations focus on protecting citizens, and position food sellers as a potential threat to that citizenry. While food cooked in an unhygienic environment is certainly a public health threat, it is important that these workers be given the recognition they deserve as key players in local economic development. They contribute to tax revenue, they provide employment, and they provide an affordable service to citizens.

Improved recognition must necessarily include an understanding that basic urban services such as sanitation, access to clean water and waste management are part of a system of economic rights. Local governments in Ghana have in theory committed themselves to promoting local economic development. If they are serious about this, as well as about protecting the public health, then more attention needs to be paid to the ways in which healthy working environments can be incentivised in collaboration with food sellers. The cost and delivery of basic services and infrastructure should be better controlled, and urban health regulations should look to support these workers, rather than continually punishing them for operating in an unhygienic environment that is largely the result of structural and infrastructural factors beyond their control.