Tracing a line through a fractured Palestine, from Arroub to Bethlehem

In late 2012, six researchers set out on a hike in the Palestinian territory of the West Bank, seeking to trace the route of an ancient Roman aqueduct. What should have been a simple journey becomes fraught with geopolitical complexities as the group transgresses the various spatial regulations that fragment the territory. Yet the journey also produced a sense of continuity that has become all but forgotten, as Thayer Hastings reports.

Late in the autumn of 2012, a group of six researchers set out on foot across the West Bank, starting near Arroub, a Palestinian refugee camp in the southern lobe of the territory, where an ancient and magnificent pool built by the Romans to store water now accumulates garbage blown in by the wind. From there, the group began walking towards Solomon's Pools, three further massive stone tanks just south of Jerusalem, attempting to follow the route of a Roman aqueduct connecting between the two points. I joined them on their second day.

The valleys between Arroub and Jerusalem contain several small Palestinian towns and villages. Bethlehem, a city of over 25,000 residents south of Jerusalem, is the largest urban centre en route. Along the hilltops jut a number of scattered but networked Israeli colonies.

Our hike fell around the olive harvest season in late autumn; aged tree trunks thickened our view of the farmlands we passed. For the most part we kept to rocky and barren routes between patches of yellow thistle or followed any roadways heading in the right direction.

Charting our way across the hilly terrain in search of the elusive remains, we looked for clues — the flow of the topography, rocks hand-hewn for ancient piping. Reviving a forgotten path, we reconstructed the aqueduct in our imaginations. But we also reconstructed the continuity of a rolling Palestinian landscape interrupted by the physical legacy of the conflict with Israel.

The most visible aspect of this legacy is the separation or annexation wall being built by the Israelis since 2002, which strays far from the 1967 ceasefire line (the "Green Line"), carving out almost 10% of the West Bank for incorporation into Israel proper. But other, invisible boundaries crisscross the landscape, signifying Israel's current claim to the terrain. The language of the Israeli occupation designates certain lands as off-limits to Palestinian residents with terms such as "military zones", "seam zones" or "firing zones", and follows an alphabetical terminology of Areas A, B and C to describe relative degrees of civil and military administration.

The hike dealt with none of these lines directly, but rather offered a subversive challenge by stepping into a time before the current apartheid-reality existed: before the wall, before the colonial parcelling of Palestine, before the displacement of 800,000 Palestinians during the 1948 Nakba ("catastrophe").

Undergirding the trek was the act of stitching together a fractured social geography. The (mostly) invisible political lines dropped across the hills writhed underfoot constantly compelling one to reflect on who is within and who the "outsider".

Connecting the camps

The hiking project, entitled "In between camps", emerged from Bethlehem-based Campus in Camps, a programme developed by Al-Quds University, and which has been described as the first university in a refugee camp. Its foundational philosophy is to foster new forms of self-representation amongst Palestinian refugees. As one of the participants in the "university in exile"'s curriculum, Saleh Khannah initiated the hiking project, primarily in order to reactivate the site of the Roman pool near the Arroub refugee camp.

The Arroub camp is home to 8,000 people brought together from 33 depopulated Palestinian villages located in Israel proper. Most residents come from Iraq Al-Manshiyya, Zakariyya, Aggour and Qustantinya villages. In Arabic, the name al-Arroub means "fresh water". Plentiful water was a main reason Palestinian refugees from 1947 - 1949 escaped to this site. The original refugees and their descendants have sought their right to return and repatriation since those days, though that right is denied, with international complicity.

Khannah was born and raised in Arroub, though his family had been forcibly displaced from Zakariyya in 1948. He is one of 4.8 million Palestinian refugees in the UN Relief Works Agency's (UNRWA) register; another estimated 2.6 million Palestinian refugees go unregistered.

For Khannah and the project's other visionaries the hike intended to explore the concept of relation. In a booklet compiled by participants, Giuliana Racco writes: "The ancient structure (now for the most part destroyed) places two contemporary camps, Arroub (near Hebron) and Dheisheh (near Bethlehem), in relation to one another, and these camps are likewise both related to Jerusalem via this conduit constructed by the Romans — ancient colonizers of the area — crossing territories which are at times prohibited to the locals — Palestinians, due to the current situation of rule."

A "careful" encounter

The reality for Palestinians in the West Bank is one of extremely limited contact with Israelis, either by looking from afar at colonisers of the hilltops or oppressive exchanges with soldiers enforcing the occupation.

At the end of the first day, two Israeli military jeeps suddenly appeared from the roadside. Four soldiers emerged and approached the group asking what the seemingly out-of-place hikers were doing and where they were from.

One of the internationals amongst the hikers responded to the soldiers' enquiries. "We are from Italy", said Diego. The soldiers were noticeably suspicious, particularly apparent when they stared at the Palestinians, distinguishing them by their skin tone and dress. The group applied a tactic of information overload: we are hiking … in search of an ancient Roman aqueduct … look, here is a map …

The soldiers did not request anyone's identification cards; on the other hand nor did they offer any useful suggestions for the hikers' search. The outcome of the interaction was to continue unhindered. "They gave us one piece of advice," said Khannah: "They told us to be careful. I understood it as, 'be careful of Palestinians.'"

Lines of flight, lines of separation

The French philosopher Gilles Deleuze has said: "in a certain sense … what is primary in a society are the lines, the movements of flight … in a society, everything flees … a society is defined by its lines of flight." As a whole but to varying degrees, Palestinians are pressured to flee while Jewish Israelis are encouraged to replace them.

And Nurit Peled-Elhanan, an Israeli academic who has written on the presentation of Palestinians in Israeli schoolbooks, states that maps — visual depictions of these lines of flight — "are political tools that transmit the messages they intend to transmit." Primarily, the tangled lines imposed by Israel intend to demarcate access to various spaces according to a gradient of rights applied to the different categories of person under its hegemony.

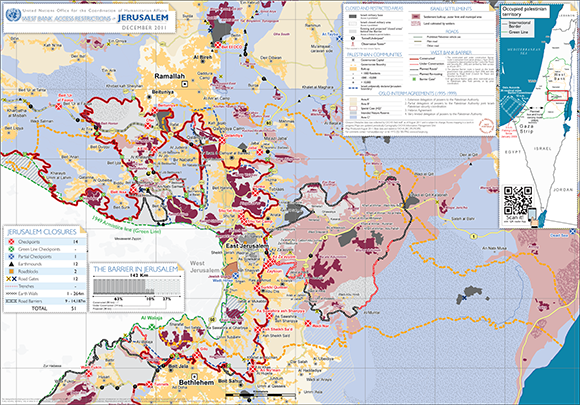

Zooming in on Jerusalem shows the limited mandate of the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) ending at the increasingly irrelevant 1967 Green Line. UN maps are regularly updated in response to Israel's expanding settlement projects; this map was produced in December 2011.

Despite the seeming strictness of the lines as they appear on maps, Israel has never declared its borders, enabling it to continue territorial expansion without revising political positions. Vague official borders are paired with an elaborate system of separation practices. In the West Bank, a regime of checkpoints and permits is designed to bar Palestinians from the territory Israel currently colonises, and restrict Palestinian use of the territory it intends to colonise in the future. Often the regime manufactures messages meant to relieve cognitive dissonance, such as "security fence" for what is really a wall of annexation. In practice, the wall embodies imprisonment rather than security, delineating an "us" from a "them" at the cost of the security of the latter. Enforced human classification of insiders and outsiders, obvious to the disenfranchised, betrays the public persona of the state as defender of the common good.

A map of the West Bank village of Walaja released by Israel in July 2012 shows the intended and in-progress plan for the wall that will encircle the residents, isolating one home in an individual prison accessible by tunnel and place two homes within a concrete corridor. The purple areas represent the wall of annexation.

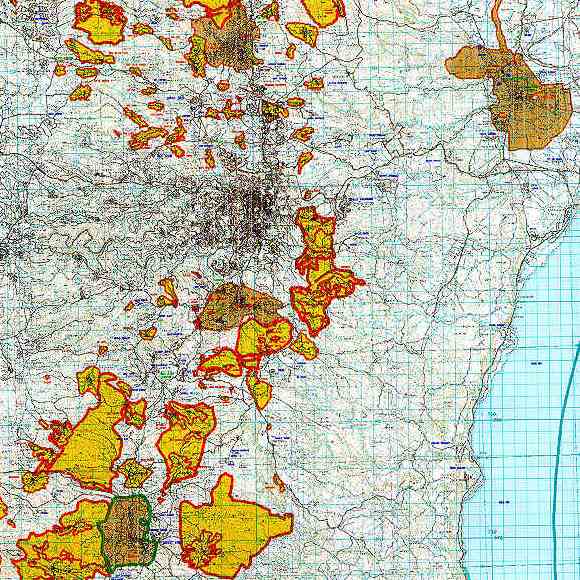

The Oslo negotiations between Israel and the Palestine Liberation Organization during the 1990s shaded the map of the West Bank into Areas A, B and C where the newly created Palestinian Authority and Israel have since collaborated on administrative and military control of the territory. The cartographic partitions are embedded with regulations such as the prohibition of Israeli citizens from Area A of the West Bank (18% of the territory, where most West Bank Palestinians live and which is under the administration of the Palestinian Authority). While in practice Israel rarely enforces this law for Palestinian citizens of Israel, mixed-demographic Palestinians are officially prohibited from group hikes across this mosaic of geographic separation, which is even stricter within Israel proper.

An extract of the Israeli-Palestinian Interim Agreement map from the 1995 Oslo Agreement, depicting Areas A and B of the West Bank. Jerusalem is in the centre, Hebron to the southwest, Ramallah to the north and Jericho to the northeast.

Khannah's band of hikers was composed of foreign passport holders, West Bank Palestinian residency card holders and me, a Palestinian with Israeli citizenship. The hikers were united by a shared experience, but technically each individual faced specific restrictions based on the lines of the contemporary political map that he likely crossed. Palestinian citizens of Israel are prohibited from entering Area A, which is "dangerous" according to the Israeli signs positioned as helpful reminders. West Bank Palestinians are forbidden from entering Israel proper which, unlike the restriction on citizens in Area A, is enforced with rigidity. Foreigners are permitted everywhere in Israel/Palestine except Gaza, but are advised to avoid mention of travel to the West Bank when passing through Ben Gurion International Airport.

One might say that Israel categorises Palestinians into four groups on a spectrum of more rights to none: citizens of Israel, Jerusalem residents, West Bank residents, Gaza residents and the fifth non-category of exiled refugees, dispossessed of any rights to their homeland. This contrasts with the status of Jewish people in Israel who hold citizenship and nationality. While these are often synonymous terms in other countries, here full national rights are categorically unattainable for Palestinians and are the linchpin of ethnicity-based inequality.

The problematic position of Palestinian citizens of Israel evokes one of the most convoluted messages of the Israeli regime. 1.5 million Palestinian citizens are legally and socially unequal to Jewish Israelis despite their citizenship. More than 50 Israeli laws discriminate against them in all areas of life. For example, the Citizenship and Entry into Israel Law specifically targets Palestinians by refusing them the right to family unification. Palestinian spouses from the West Bank or the Gaza Strip are prohibited citizenship, residency or permits required for crossing the Green Line into Israel. Paired with the prohibition of Palestinian citizens from Area A of the West Bank and the absolute disconnect from Gaza by the siege, the Israeli legal system effectively forbids coupling across the three political territories within the homeland.

Unlike Palestinians, Jewish Israelis are encouraged to live a seamless existence within a contiguous "Greater Israel" complete with highway infrastructure linking West Bank colonies to Israel proper without exposure to Palestinian urbanity. The arrangement results in a semblance of contiguity for Jewish citizens. For Palestinians, however, the Green Line is solid. While thousands of Palestinian families defy the separation principle embedded in the Citizenship Law, many others are effectively expelled from the country due to a combination of factors that make life unbearable.

The state justifies physical and legal separation with arguments about "security", but unravelling it reveals mechanisms coordinated to secure specific demographic outcomes. In total, the Israeli ethnocratic system, the wall and other barriers fracture the five million Palestinians currently within Israel/Palestine into more manageable political and economic entities while encouraging their emigration from "Greater Israel". Most of the boundaries depicted on contemporary maps are spaces of encroaching colonisation and, on the other hand, forced expulsion. Since 1947, waves of displacement have torn through Palestinian society, and as a result, six million Palestinians reside in the Shatat, or exile community, outside of Israel/Palestine.

A new landscape of public spaces

On the second day I joined the hikers in Tuqu', a village south of Bethlehem. Stumbling gradually into wakefulness in the early morning sunlight, we spread into the hills searching anew for signs of the aqueduct. After a few false alarms we decided to head in the general direction we believed the water system laid, inevitably encountering the area's residents. Khannah tasked himself with determining the most knowledgeable-looking individuals to ask for directions. They were almost always elderly male farmers. We met an aged man with missing teeth accompanied by his son of around 40 years. They seemed proudly familiar with the aqueduct and described a detailed route to a point where we would re-emerge in its tracks. They were right.

We reached Solomon's Pools, a park area shaded by sturdy trees featuring three stone basins lined in a row that had once functioned as the main water vestibules for ancient Jerusalem. The Palestinians of Irtas (the town where the pools are located) and Dheisheh (the nearby refugee camp), and picnicking visitors use the site as a common public space, the lack of which is a defining feature of many densely populated and spatially restricted refugee camps. Solomon's Pools Resort and Convention Center recently won a bid to develop a private park at the site, fundamentally altering the way the space will be used and, most importantly, who can use it.

Having hiked more than 40 kilometres over two days, on a third outing we made a return to Arroub's Roman pool, walking back to initiate the process of "activating" the site of origin. We spent an afternoon cleaning the ancient pool. As Khannah put it, the pool is an underutilised venue. He envisions transforming its current appearance as a crater in the landscape into a public space available for leisure, concerts and educational activities for the Arroub community inside the pool area, surpassing the vision for the use of Solomon's pools at the other end. Although unattended and antiquated, the pool serves as a connection to a Palestine of the past and the symbiotic relationship with what is currently a largely off-limits Jerusalem.

Confronting an abnormal urbanism

Intending to visit Arroub several weeks later, I was advised by Khannah not to come as Israeli soldiers had been invading the camp on a daily basis, and that particular Sunday was exceptionally harsh with many cans of tear gas, sound bombs and rubber-coated bullets fired. Not long before, a 21-year-old woman from the camp had died from a live bullet to the head on January 23rd when Israeli soldiers fired on her and her friend while they walked through their college campus. I heeded Khannah's advice and waited for the following week.

That following week, entering the camp from the main road, I passed two haughty Israeli soldiers who had paused to reload their guns with tear gas canisters. Perhaps because I looked like an outsider, they held off from resuming firing until I had walked around the bend in the road and out of sight. Around the curve were a dozen charged youth — mostly children — some of whom held rocks to ward off the soldiers. The noxious gas was enough encouragement to hurry along without the concerned warnings from residents on the street. Once inside the office with Khannah and two other participants of the hike, we tightly shut the doors and windows against the stinging tear gas that had infested all corners of the camp.

In order to offer useful direction, the map used on the hike was older than the political reality that exists today. Outdated enough to recognise the aqueduct's path as a significant marker, the map also provided relief from the web of political lines that bind Palestinian space. The purpose of the project — to reactivate the water system's source — was a modest objective with profound implications. Tracing a geographic contiguity across the Palestinian hills reasserted a sense of belonging and confronted the ideology of dispossession built into the fracturing regulations imposed by Israel. By linking abnormal political spaces and challenging those boundaries, the process of hiking excavated layers of exclusion.