A city doesn't need a centre! (But it does need realistic planning)

The cities of the twenty-first century are too big for our transport planners to rely on the old hub-and-spokes models on which our existing networks are founded. Cities like Los Angeles, London and Sydney should be planned as metropolitan tapestries, with multiple commercial districts, grand parks and urban agriculture all interwoven with metro rail corridors, with ruthless disregard for the traditional dominance of our city centres, for our outer suburbs to grow sustainably in the coming decades.

Bernard-Henri Lévy, the French celebrity philosopher, wrote in 2006 the following:

" … what must be true for a city to be legible? First, it has to have a center. But Los Angeles has no center. It has districts, neighborhoods, even cities within the city, each of which has a center of some sort. But one center, one unique site as a point of reference … nothing like that exists in Los Angeles … "

He went on to lament that such a city:

" … is, I fear, a city about which one can predict with some certainty that it will die."

But why should a city need a centre? In an age of urban mega-regions, where urban areas are increasingly open territories comprising a network of cities, is there still any purpose in identifying one centre amongst them?

Most older city centres have been subject to an upward spiral of infrastructure investment, with each project seeking vainly to reduce the increased congestion created by the last generation, to the neglect of the outer suburbs. The supposed importance of the centre is a self-fulfilling prophecy.

What is a centre? Often it is the older, historic district, a cluster of political institutions and monuments, or a busy commercial and office precinct, bristling with skyscrapers. But none of these need to be at the centre of a large city, nor in the same place, and it would make for better planning if we abandoned the myth of the city centre altogether.

Rather than think of a city as a centre surrounded by suburbs (the hub-and-spokes model), think of it as a patchwork of specialised districts woven together by a carpet of housing and transport. For the efficiency of each industry, similar businesses cluster in specific districts. The financial districts of New York's Wall Street and Paris' La Défense are perfect examples of this, as are Los Angeles' film studios in Hollywood and Westside and the post-production units in London's Soho. Most large cities have specialised districts for food wholesaling, garment industries, electronics, and you can think of many more.

But none of these sectors have special claims to any city's centre other than by historical accident. Older cities have necessarily invested many more years of infrastructure planning into their central districts than their growth-ring suburbs, but this has been perpetuated in recent years by a false belief. As Jarrett Walker explained earlier this week, public transport does not reduce congestion, (it increases a city's commuting capacity) but in the past, politicians and transport agencies believed that it did. Most older city centres have been subject to an upward spiral of infrastructure investment, with each project seeking vainly to reduce the increased congestion created by the last generation, to the neglect of the outer suburbs. The supposed importance of the centre is a self-fulfilling prophecy.

When cities have invested in less central areas with equal intensity, they have generally succeeded in creating new business districts and expanding their commercial capacity. La Défense and London's Canary Wharf were both given new rail lines, new arterial roads and special planning instruments, just like the city centres.

In mega-cities like Tokyo, Delhi and Los Angeles, and in mega-regions like the Pearl River Delta, a hub-and-spokes model is entirely inappropriate to their sprawling scale. Such areas can accommodate multiple business districts, multiple wholesaling districts, multiple administrative quarters, that make the idea of a city centre rather quaint.

Planning without a centre

Large cities today need to be planned not in concentric circles, but as tapestries. We still need differing degrees of intensity across urban areas, but these should be planned as an orderly modulation of intensity throughout the metropolis. We must plan busy commercial cores and quiet residential and recreational areas in alternance.

And we must invest in those outer-suburban commercial cores the way we used to invest in city centres — by throwing all our political might behind them. We cannot talk of satellite cities, since cities so conceived will always defer to an overburdened centre. We must choose which of our outer suburbs will become commercial hubs to rival the central business districts, and invest in them accordingly. This doesn't need to mean a forest of skyscrapers; building a compact urban heart like Barcelona delivers a similar degree of density.

We cannot talk of satellite cities, since cities so conceived will always defer to an overburdened centre. We must choose which of our outer suburbs will become commercial hubs to rival the central business districts, and invest in them accordingly.

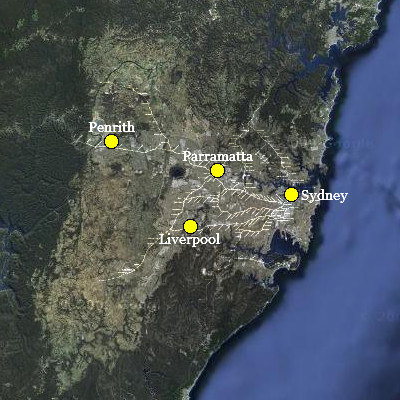

My favourite illustration of this remains my native Sydney. Seen from satellite, metropolitan Sydney takes a hammerhead shape hemmed in by hilly bushland. The coastal suburbs around the city of Sydney are squeezed in between the tributaries of the harbour and the Georges River, while the western suburbs have far more room to spread out.

Base map © Google / TerraMetrics See original

Sydney's three "satellite cities", Parramatta, Liverpool and Penrith, each 15 to 25 kilometres apart, stretch out into the western plain. There are two million residents to the east of Parramatta, and two million residents to its west. As the Sydney region has grown, the "centre" looks decidedly more out of place. Yet all of Sydney's rail infrastructure, shown as white lines, now and planned into the future, focus like an array of darts upon the eastern centre, with almost nothing in the west, retaining a lopsided hub-and-spoke model at odds with the geography of the region.

Planners ought to treat the western plain as a tapestry, through which be woven buzzing commercial centres, grand suburban parks, urban agriculture, and cleantech industrial areas. Rather than the existing low-volume bus routes, new high-volume rail lines should criss-cross the western suburbs, creating new density hubs where they intersect. The three satellite cities should be developed as densely as today's Sydney to accommodate future business growth in the metropolis, relieving commercial pressure on the harbour. And Parramatta ought to be a household name internationally, at least among urbanists, just as Canary Wharf, La Défense and Tokyo's Shinjuku are now.

Planners are often fearful of proposing major transport investments in outer suburbs. Where they do, it is often low-volume modes, such as the Liverpool-Parramatta T-way bus route in Sydney, the Tramlink in London's southern suburbs, or the T1 and T2 tram lines outside Paris.

But if we believe that all residents deserve sustainable transport, not just the "inner city", then we must propose much heavier infrastructure projects for our growth-ring suburbs. And if we must consolidate our cities to reduce their carbon footprint, then the best way to avoid further overcongestion in their centres is to build more public transport in the outer suburbs, not in the centres.

Earlier this month, our London columnist Joe Peach proposed that his city's outer boroughs develop their own transport systems, with dense bus networks like those of Reading and Brighton the most economical solution. I believe it is an excellent strategy that outer suburbs can take into their own hands, but I also maintain that a metropolis the size of London needs heavier rail infrastructure to integrate such local networks into a single, dynamic and equitable economy.

Cities will always have monuments, landmarks and icons that capture the imagination of their inhabitants. But these can no longer structure the whole layout of a city as they once did, because our cities and mega-regions are of a vastly greater scale than those of the nineteenth and earlier centuries. Inhabitants will always think fondly of these places as the centre of their cities, and tourists like Bernard-Henri Lévy will continue to search for them. But planners must be a lot more professional, and plan for a much more equitable distribution of infrastructure and business across the metropolitan landscape. A city without a centre will thrive if its tapestry of infrastructure is rich, but a city dominated by its centre is one whose outer suburbs will certainly languish.